CSCE 121: Introduction to Program Design and Concepts

Lab Exercise Three

Objective

The aim of this lab work is to continue practicing to writing functions. As a reminder: by factoring problems into smaller pieces. That helps in making your code easier to read, but also simpler to debug, and use again for subsequent projects (and labs). Try to think about decomposition into functions as a guide in actually solving the problems. When I'm stuck I often find that is because I'm trying to bite off too much in one function; splitting it into smaller more manageable pieces helps a lot.

How far must I get?

This lab is assigned for the entire week. You should complete the questions that you're not able to finish in the lab session on your own. If you are finding it tough to keep up the pace, it may be wise to look over the questions and make a first attempt before arriving at your lab session. That way you can use the time most effectively in getting help with the questions that are sticking points for you.

Basic Sums

Write a function SumOfNums that calculates and returns the sum of

the numbers from 1 to n (where n is a positive integer parameter). The statement

cout << SumOfNums(100);

should cause "5050" to be printed since 1+2+⋯+100 = 5050.

Solve this problem without using strings—we've not covered strings in class yet—clear thinking and

ints are all you should need. If you feel that you need to convert the input to a string, that is because you're trying to pull off a single digit.

Just write a function to do that using arithmetic!

Summing Digits

Write a function SumOfDigits that takes as a parameter a non-negative integer x and calculates the sum

of the (decimal) digits that comprise x. For example, the line

cout << SumOfDigits(15290);should print "17" because 1+5+2+9+0 = 17.

For this exercise, it might be helpful to declare some variables of type long rather than int to give you the chance to test some

longer, more juicy, instances.

|

|

smuS

Write a function SumWithDigitsReversed that takes a (non-negative integer) parameter x, and sums

x with the number constructed from x with its decimal digits reversed. For example, the line

cout << SumWithDigitsReversed(15290);

should produce "24541" since 15290 + 09251 = 24541.

|

|

Numbers I

Write a function that determines whether its input is a prime number. The following is how you might start the definition of the function.

bool is_prime(int n)

{ // returns true if and only if n is a prime number

...

}

Numbers II

Using your function from the previous question, prompt the user for an upper bound, then print all primes up to that number. Below is an example. You should attempt to match the output format exactly.

Enter an upper limit: 72

2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71

Numbers III

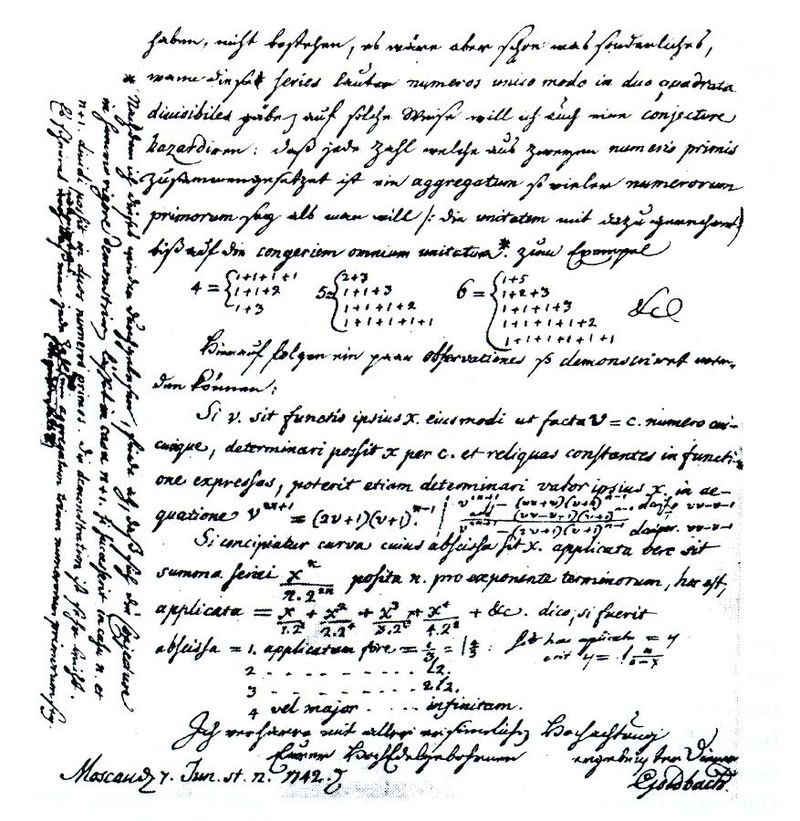

First asserted in a letter penned to Euler in 1742,

Goldbach's conjecture states that:

every positive even number greater than 2 is the sum of two

prime numbers.

Examples: 42 = 5 + 37, 16 = 3 + 13, 64 = 3 + 61.

Write a program that asks for an integer and, after checking that it is even and greater than 2, prints two primes whose sum is the input.

The statement above, though simple, is one of the most famous facts of number theory whose

proof remains elusive. Actually, the wording above isn't exactly how

Goldbach expressed the claim to Euler, you can see the equivalent original

statement in the associated Wikipedia

article if you are interested. It has been verified to be true up to

enormous numbers (far, far larger than our puny int variables

will hold), so if your program can't find a pair that is a bug in your code.

Logic

Leap Years

Write a program that prompts the user for a year and then provides an output

indicating whether that year is a leap year or not.

The rule for the Gregorian calendar, is as follows:

A year is a leap year if it is divisible by 4,

unless it is divisible by 100 in which case it is not, unless it

is divisible by 400 in which case it is.

What are good test cases for your program?

Implementing Nand, Nor, and Exclusive-or

In class we saw the operations that C++ uses to represent logical and, or, and not operations. Three other common ones are nand, nor, and exclusive-or. Logical operations are often described using tables, which give a value for all possible input combinations. The three tables below specify nand, nor, and exclusive-or, respectively. You read the table as follows: pick the column representing the first input, the row representing the second input, and the value at the intersection of the row and column is the output of the operation.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Write functions that compute these operations. Below are three definitions to copy-and-paste into your editor for use as a starting point.

bool nand(bool a, bool b)

{ // is (a NAND b)

...

}

bool nor(bool a, bool b)

{ // is (a NOR b)

...

}

bool exclusive_or(bool a, bool b)

{ // is (a EXCLUSIVE-OR b)

...

}Efficient Integer Powers

Because multiplication is a fairly involved process, in the interests of speed it is common to seek ways to minimize the number of multiplication operations needed to arrive at some result. Consider the following example, where we're raising a number to the fifth power.

A naïve approach is simply to multiply a number by itself over and over again:

565 = 56×56×56×56×56 = 550731776. Needs a total of 4 multiplications.

Oftentimes we can do better. Here we can see that by using squaring we can save a multiplication. Raising to larger powers can yield larger savings.

Step 1: Let u = 56×56

Step 2: Now let v = u×u

Step 3: Then 565 = v×56 = 550731776. Gives the result in a total of 3 multiplications.

In this exercise you'll write a function to raise a number to an integer power using this repeated squaring approach. It is broken into pieces to provide some guidance.

The Easy Powers

The first step is to ask which powers can we get just by squaring?

Well if we're given b and m and asked to compute bm then if m = 2 it is easy. Squaring twice gives the solution easily when m = 4, and doing it three times when m = 8. Obviously the pattern emerging here is that when the exponent is a power of 2 we can get the solution in a straightforward manner.

int raiseExpPow2(int b, int m)

{ // compute (b^m) when m is a power of two.

...

}

General Powers

The pattern that shows how to proceed for other exponents may also be obvious if

you're comfortable with numbers in binary (i.e., base 2).

In the example given above, the exponent was 5 and, expressing the number in binary, we see that 510 = 1012. (Where

I've used the fairly standard practice of having

the subscripts indicate the base of the number system.)

To get 565 we computed it as:

565 =

(562)2

× (56).

More generally, you can compute bm by using your function

raiseExpPow2 and the binary digits of m.

The really great news is that in the "Summing Digits" exercise above, you were

able to pull off the digits of a number. In that case you did it base 10, but

the same process will pull them off base 2.

A smart thing to do is generalize the functions you wrote for "Summing Digits" to take the base as a parameter. Next, write a function to raise b to an arbitrary (positive integer) m.

int raiseExpPow(int b, int m)

{ // compute (b^m) when m is any positive integer

...

}

Smarter Binary Digits

So far so good but if you're doing divisions (likely both / and

%) to get the binary digits (bits) of the exponent, then you're

actually doing more work, not less.

The trick is that since the machine actually represents the numbers in base 2, it is extremely easy to get the bits directly. (This is like how, when you were in grade school, you didn't have any trouble with the 10 times table—the base trivializes things.)

Here is a function that will give you the ith bit of a number.

Be careful. It is especially deceptive because we've seen both the

>> and the & before (we'll see much more of

that last character). They're being used to mean entirely new things in this code.

int getBit(int n, int i)

{ // gets the value of the i'th bit of n

// where they are labeled right to left, starting from 0.

// The "units" are at 0, (so even or odd numbers alter this entry)

// The "twos" at 1, etc.

return (n >> i) & 1;

}

In the code above, the >> means bitwise right shift.

And the & performs the bitwise logical and operation.

This page details bitwise operations in C and C++.

Improve your raiseExpPow to use these bitwise operations so

as to avoid the divisions by 2.

Puzzling*

If you've finished the lab early, here's something to tickle the gray matter:

“Four people need to cross a rickety footbridge; they all begin on the same side. It is dark, and they have one flashlight. A maximum of two people can cross the bridge at one time. Any party that crosses, either one or two people, must have the flashlight with them. The flashlight must be walked back and forth; it cannot be thrown, for example. Person 1 takes 1 minute to cross the bridge, person 2 takes 2 minutes, person 3 takes 5 minutes, and person 4 takes 10 minutes. A pair must walk together at the rate of the slower person's pace. For example, if person 1 and person 4 walk together, it will take them 10 minutes to get to the other side. If person 4 returns the flashlight, a total of 20 minutes have passed. Can they cross the bridge in 17 minutes?”

— Levitin & Levitin [2011].

* This is material outside the scope for lab quizzes.

Acknowledgements

The exercises based on digits of integers are based on questions on SPOJ. The copy of Christian Goldbach's letter is in the public domain. The bridge-crossing puzzle is from Anany Levitin and Maria Levitin, "Algorithmic Puzzles", Oxford University Press, 2011.