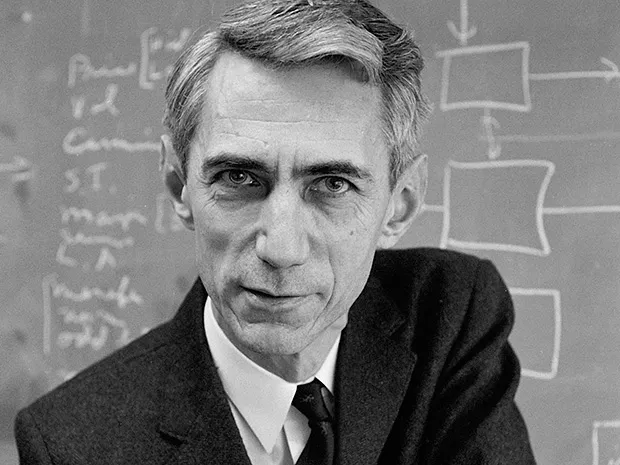

.jpg) Photo: Alfred Eisenstaedt/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Photo: Alfred Eisenstaedt/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

While I was doing research for a biography of Claude Shannon’s graduate advisor, Vannevar Bush, I learned that Bush’s mentorship of Shannon in the fields of electrical engineering and applied math decisively influenced Shannon’s career choices and thus the history of computing and digital media.

Early on, Bush recognized Shannon’s singular talents. In a 1939 letter, Bush described his then 23-year-old student as a peculiar “genius” poised “to accomplish something striking and even useful.”

Shannon did just that in the 1940s. While at Bell Labs he published a series of seminal articles in highly technical journals. The papers, which aimed to solve practical problems of telephony, launched a revolution. In “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” published in 1948, Shannon presented a unifying theory for the transmission of information that could be applied to telephones, radio, television, or any other system. By viewing all forms of information as reducible to binary digits, Shannon hypothesized that these bits—a term coined by a Bell Labs colleague—could be transmitted, error-free, even through a “noisy” communication channel.

Of all Vannevar Bush’s legacies—he organized the Manhattan Project, after all, and built powerful analog computers in the 1930s—one of his greatest was certainly his support and encouragement of Shannon.

The centennial of Shannon’s birthday will occur on 30 April, and amid the celebrations few will recall that his insights were also distorted and misunderstood. As the years passed and fulsome praise arrived, Shannon grew enigmatic and withdrawn. Prone to pranks and gambits, such as building unicycles and juggling obsessively, he matched the acclaim with modesty. His theory of information, he wrote in a brief 1956 article titled “The Bandwagon,” has “perhaps been ballooned to an importance beyond its actual accomplishments.” He continued, “Authors should submit only their best efforts, and these only after careful criticism by themselves and their colleagues.” He worried that his insights were being “oversold.”

Historians Paul Nahin and William Aspray have convincingly shown that Shannon was correct to want to share credit. He built his theories on the shoulders of earlier giants, notably his personal hero, George Boole, the 19th-century logician. “It is because of Shannon that Boole is rightfully famous today, but it is because of Boole that Shannon first gained the attention of the scientific community,” Nahin wrote in his joint biography, The Logician and the Engineer.

What then would I tell Shannon were I to meet him while wandering through those corridors at MIT? I would not dare risk his displeasure by joining the “bandwagon” and proclaiming him “the father of the information age.” Rather, I would say that the signal lesson of his career stems from how he pursued knowledge about the world. Shannon showed that engineering creates new knowledge as readily as science does and that, moreover, engineering practice can precede scientific theory.

Shannon’s life exposes the fiction that, in the creation of knowledge, theory must always precede practice and that engineers with “dirty hands” can never spawn the rich ideas that scientists later spend generations extending, revising, and deepening. While Shannon deserves acclaim for launching the digital revolution, his centennial is equally an occasion to celebrate all those persistent practitioners—those use-inspired problem solvers—who endure the condescension of gazers at stars and navels.

To those who insist that practice can never give birth to new pathways of inquiry and paradigms of knowledge, Shannon provides the definitive negative confirmation. And that is worth celebrating on Shannon’s birthday, or any other day.

About the Author

G. Pascal Zachary is a professor at Arizona State University’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society and is the author of Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century (MIT Press).

For nearly 40 years, Zachary has been fascinated by the role of engineers in innovation and their relationship to science, politics, and culture. He is the author of Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century, and Showstopper, about the making of a software program. At Arizona State University, where he is a professor in the university’s school of innovation, he teaches courses on the past, present, and future of technological change. Zachary began his social studies of engineering as a journalist, reporting on Apple and computing for newspapers in San Jose. In 1989, he became the chief Silicon Valley reporter for The Wall Street Journal, where he was senior writer until 2002. He later wrote columns on digital innovation for The New York Times, Technology Review, IEEE Spectrum, and other publications. Zachary’s work grew increasingly international in the 1990s, when he traveled extensively to technology enclaves in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe. In 2000, he published The Global Me, a book on multicultural identity and the new world economy; a revised edition, incorporating the crisis engendered by 9/11, was published in 2003 as The Diversity Advantage: Multicultural Identity in the New World Economy. Zachary maintains a strong interest in sub-Saharan Africa, and in many of his more than 50 research visits to the region he has concentrated on the relationship of technology and development. He is the author of a memoir, Married to Africa: A Love Story, and a collection of essays, Hotel Africa: The Politics of Escape. In 2017, he completed a three-year study of the growth of computer science at universities in Uganda and Kenya, a project funded by the National Science Foundation. Zachary’s writing has been described as “deeply informed and insightful” by The New York Times, and The Atlantic has called him “a serious public intellectual who can combine familiarity with the scholarly literature...and first-hand reporting.” To learn more about Zachary, see www.gpascalzachary.com.